The Convergence of Politics, Military Necessity, and the Atomic Bomb: A Deeper Dive into World War II's Endgame

The cataclysm that was World War II rumbled towards its devastating crescendo with a complexity often glossed over in simplified historical narratives. The war’s conclusion, particularly in the Pacific Theater, was a chessboard mired in political gambits, military desperation, and new, unprecedented technological terror—the atomic bomb. This analysis will siphon through the intricate layers of these elements, providing a nuanced understanding of how multifaceted the road to Japan's surrender truly was.

Rethinking the Role of the Atomic Bomb

It's a prevalent myth, tightly woven into the fabric of World War II's history, that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the unilateral events that jolted Japan into surrender. However, a deeper scrutiny suggests a more tangled truth. The bombings were undeniably influential, serving as the fulcrum for Emperor Hirohito's unprecedented intervention in government to sue for peace. However, they were not sole actors in this drama but part of a wider constellation of forces pressuring Japan.

The decision to deploy these bombs was not made in isolation. It emerged from a context where traditional bombing raids had already scalded Japan's cities into landscapes of ash, and where a ground invasion might have elongated the war, exacting a horrific toll in human lives. The atomic bomb, terrifying in its efficiency, offered a shock that traditional bombings could not—a shock that could potentially offer an expedient end to hostilities.

The Soviet Factor

While the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are often spotlighted, the Soviet Union's actions in Manchuria are less illuminated in popular recountings of the war. The Soviet invasion, executed with ruthless efficiency, dismantled the Kwantung Army, Japan's last bastion of military strength in mainland Asia.

This narrative adds an essential layer to our understanding: while Japan was reeling from internal devastation, a significant external threat loomed. Stalin’s decision to move into Manchuria was not merely a military action but a geopolitical strategy, influenced by the demonstration of the atomic bomb's reality. Stalin, initially skeptical of the bomb’s existence, was spurred into action by the irrefutable evidence of its destructive capabilities, aiming to secure a stake in the post-war restructuring of the Pacific.

Political Maneuvering at Potsdam and Beyond

The geopolitical chess game of the Potsdam Conference set the stage for these world-altering decisions. Truman, aware of the successful test of the atomic bomb in New Mexico, navigated these negotiations with a new level of confidence. His objective was clear: limit Soviet influence in post-war Japan. This was a world of realpolitik, where the emerging Cold War dictated not just military decisions but the future political landscape of Asia.

The timing of the Soviet invasion, strategically placed between the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was not coincidental but a calculated move by Stalin, who was now keenly aware of the bomb's potential impact on the war's outcome.

The Home Front: Japan's Perspective

From the Japanese perspective, surrender was anathema. Despite facing annihilation, the militaristic mindset that permeated the leadership was prepared to fight to the bitter end, a testament to their bushido-driven ethos. However, the dual shock of atomic devastation and the Soviet offensive shattered this resolve.

The Emperor’s intervention, driven by the existential threat these events posed, was a watershed moment in Japanese history. It was not just a military capitulation but a profound cultural shift, signaling the end of divine imperatives guiding national policy.

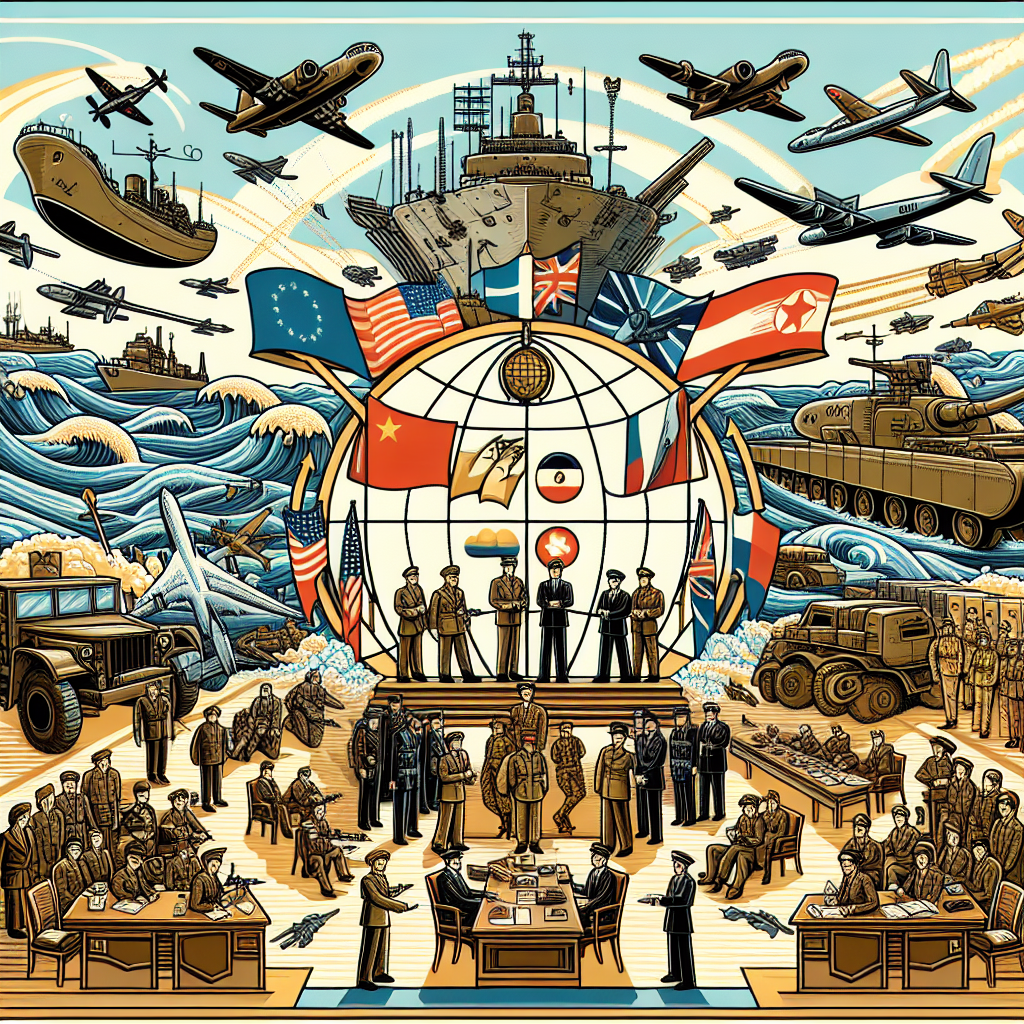

Historical Context of WWII Japan

Legacy and Lessons

The end of World War II in the Pacific was a confluence of military innovation, strategic bombings, and international diplomacy, underscored by a race against time and ideology. It marked the dawn of the atomic age, setting the stage for the nuclear arms race that would dominate global relations for decades to come.

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while pivotal, were part of a broader narrative that included significant Soviet maneuvers and intricate political negotiations. These events collectively accelerated the end of the war but also ushered in a new era characterized by Cold War tensions and the haunting presence of nuclear threat.

In retrospect, the final chapters of World War II offer critical lessons on the interplay of military necessity, technological advancement, and political strategy. They prompt a reflection on how future conflicts might be navigated or averted in an age where the specter of nuclear war still looms large.

In piecing together these myriad factors, we gain not only a fuller picture of how the war concluded but also insights into the complex tapestry of human conflict. Each decision, each action taken during those final days of the war, was a thread pulled with the hope of re-weaving the fabric of a shattered world, highlighting the enduring challenge of making choices in the shadow of monumental stakes.

Related News

- The Complexities of Japan's Surrender in World War II

- The Strategic Decisions Behind the Atomic Bombings: Unveiling Hidden Motives

- The Atomic Paradox: A Tale of Destruction and Misconception

- The Inevitability of the Atomic Bomb in a World Without World War II

- The Unyielding Spirit: Understanding Japan's Stance in World War II